As part of my M.Sc. thesis and research project at the School of Urban Planning at McGill University

Supervisors:

Professor Nik Luka, Associate Professor with the Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture and School of Urban Planning, McGill University

Professor David Wachsmuth, Associate Professor, School of Urban Planning, McGill University

This study aims to explore to what extent and under which circumstances non-commodified cooperative housing initiatives are able to provide affordable and stable living conditions to low- to median-income households in the growing crisis of housing unaffordability enacted by neoliberal housing systems and if they are able to maintain proactive social accountability through exiting links with housing advocacy groups and solidarity networks, and knowledge exchange. To address this question, long-term affordability mechanisms (policies and practices) that are imbedded into the non-commodified cooperative housing models need to be studied and understood from the perspective of regulatory mechanisms for social accountability and the dynamics between cooperative housing initiatives and housing activism, and how they contribute to housing advocacy groups, solidarity networks, knowledge exchange and mutualism from the perspective of non-regulatory mechanisms for social accountability. For this purpose, 22 interviews with experts in cooperative housing industry, housing activists and residents of six housing cooperatives will be conducted for the primary data collection in two cities with distinct contexts, Montréal, with its mature cooperative housing tradition, and Barcelona, with its emerging cooperative housing movement. The study is expected to confirm or contest the “binding” social contract that is enacted in non-commodified cooperative housing initiatives through public investment, policies, regulations and housing advocacy groups and solidarity networks involvement, as well as the following themes:

- cooperative housing initiatives are able to achieve housing affordability in a long term,

- with appropriate regulations, cooperative housing initiatives are inclusive towards low- to median-income households,

- public investment and governmental involvement are crucial for maintaining cooperative housing affordable and accessible for low- to median-income households, and

cooperative housing initiatives exist within the “right to housing” conceptual framework and tend to be involved in advocacy for housing rights, and “give back” to solidarity networks, urban-based social movements, and housing advocacy groups, as well as contribute to public discourse on housing, knowledge exchange and mutualism.

Introduction and Problem Statement

Although the right to housing, written in both Canada’s National Housing Strategy Act (2019) as a fundamental right and the Spanish Constitution (1978) as a constitutional right, is rarely exercised by citizens and governments alike. Housing is commonly treated as an asset and is placed within the economy due to its profit-generating potential, though housing is not an economic demand but a social need and the human right. Thus, by nature, housing markets cannot be efficient, as efficiency is not their goal. “[T]he social concept of need and the economic concept of demand are two quite different things and […] they exist in a peculiar relationship to each other” (Harvey, 2009, p. 154). At the same time Harvey (2009) argues that economic markets cannot be efficient without accounting for social justice, and social justice cannot be achieved without economic efficiency, which leads us to the conclusion that the issue is in how we view economic efficiency – as an extractive tool that does not account for its sustainability beyond the decision-making and well-being of a single generation. Ignoring social costs during economic activities impedes further generations to achieve economic efficiency. Therefore, the just system can be concluded as social and economic cooperation. Yet, it is not how housing markets operate, as “housing is produced in accordance with the rules of the capitalist economic system” (Marcuse, 2012, p. 215). In addition, they are “regulated by the state to maximize profit” (Marcuse, 2012, p. 215). In fact, it is a misconception to think that states do not participate in housing policy even if they indeed seem passive due to deregulation agenda. State always plays an active role in housing as it always plays an active role in allocating and distributing land and resources and regulating development. “In other words, housing markets are political” and “[t]he commodification of housing is a political project that refuses to acknowledge itself as such” (Madden & Marcuse, 2016b, p. 47). Thus, the government did not withdraw from housing, but its role changed. It still regulates the housing market, but the question is what is being regulated and for whose benefit, and in majority of cases it is the private interest (Marcuse, 2012). Moreover, “every public program to enlarge the supply of affordable housing has relied on bribing the private housing industry to make its product more affordable” (Marcuse, 2012, p. 220), including the subsidies for low-income families, voucher system to house low-income families in private rental market, etc., again allocating public money for the benefit of the private interest and capital accumulation instead of investing into social housing that will meet the population’s housing needs (Madden & Marcuse, 2016b).

While it is widely believed that municipalities are restrained in their actions by neoliberal states (Hulchanski, 2006, p. 10; Logan & Molotch, 2007; Merrifield, 2014), recent scholarly literature on progressive municipalism in Barcelona indicates that local governments play an active role in housing financialization, and under the pressure of public discourse and grassroots initiatives (Alexandri & Janoschka, 2024; D’Adda, 2021) can aid in de-commodification of housing through local policy (Alexandri & Janoschka, 2024). Madden and Marcuse (2016b) point out that the diminished alternative options to market housing stock is the core problem behind current housing unaffordability.

Since the 2008 mortgage meltdown and with only increasing financial crisis ever since, cooperative housing has received renewed attention together with a broader public discourse on affordable alternatives to the market and state-subsidized housing. The most prominent contemporary case of an attempt to go beyond the margins is Catalonia’s newly emerged right-to-use cooperative housing movement. It has prompted a political and academic inquiry into the question of potential scalability within a favourable legal and policy environment (Ferreri & Vidal, 2022).

Cooperative housing is quite unique in its ability to contribute to societal dynamics for collective action and mobilization around housing, balancing between civil society, the market and the state. It is also possible to trace how internal solidarity of cooperative housing initiatives translates into external solidarity for the broader community and housing movements. For example, affordability produced within the housing cooperative has internal and external solidarity values, as it contributes to greater access to alternative housing options for low-income households. However, policies and regulations promoting cooperative housing are technically complex across the nations and states and produce uncertain effectiveness (Ahedo et al., 2023). In addition, the decommodified aspect of cooperative housing is heavily reliant on policies, and with changes in political environment governments may change policies, which in turn can enable greater commodification of this type of housing. The role of housing movements is crucial and confirms that cooperative housing initiatives exist in conjunction with housing activism, as they tend to safeguard the model against commodification (Larsen, 2020) and contribute to social accountability.

Broader studies on cooperative housing also confirm that the model creates benefits beyond affordability. It boosts the creation of social capital: mutualism, knowledge exchange, self-governance, support networks, alternative relationships with property and land (Delz et al., 2020; Saillant, 2018), and adaptive housing typologies responsive to household growth, change or specific needs, thus ensuring stable living conditions (Lorente et al., 2023). While addressing and accommodating above-mentioned needs may carry a Machiavellian character, it may as well suggest the rethinking of housing and its functions in its core.

At the same time, cooperative housing is commonly associated with a certain degree of elitism, mainly defined by scarcity of options, its niche availability and therefore long waiting lists (Ahedo et al., 2023; Ferreri & Vidal, 2022; Lang & Novy, 2014), thus limiting its non-profit potential and contributing to its inability to go beyond the niche in the housing market so far (Ferreri & Vidal, 2022). However, with proper regulations cooperative housing can and should cater to low-income households and marginalized groups. Cooperative housing is relatively socially oriented, generally involves a broad mix of residents, and can show a certain level of external solidarity, despite being dominated by the market housing logic in most countries (Ahedo et al., 2023). But the examples where cooperative housing expanded beyond the marginalized solution for the privileged few are quite scarce and limited (Ferreri & Vidal, 2022). Cooperative housing in Barcelona is criticized similarly to elsewhere – as a privileged option for affluent social groups and in cronyism directly related to funding and subsidies allocated from the city budget (Larsen, 2020).

Interestingly enough, despite the criticism of elitism and catering to affluent citizens on the account of public investment, exactly public investments in form of partial funding, government-backed mortgages and rent supplements allow governments to impose appropriate regulations that ensure decommodification of cooperative housing and its long-term accessibility for low-income households, as it is demonstrated in Quebec and Montréal cases.

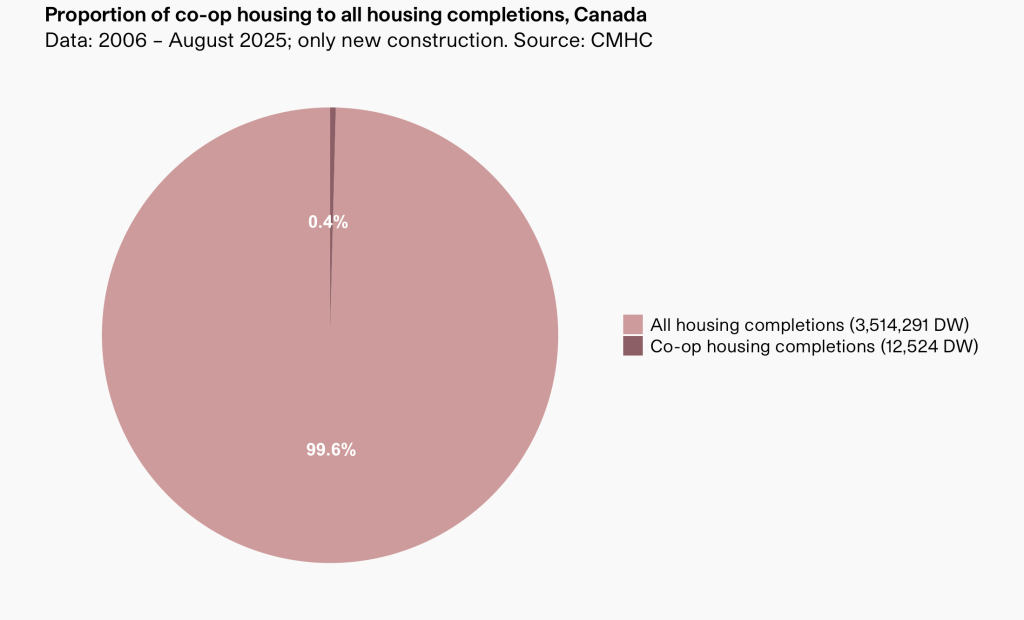

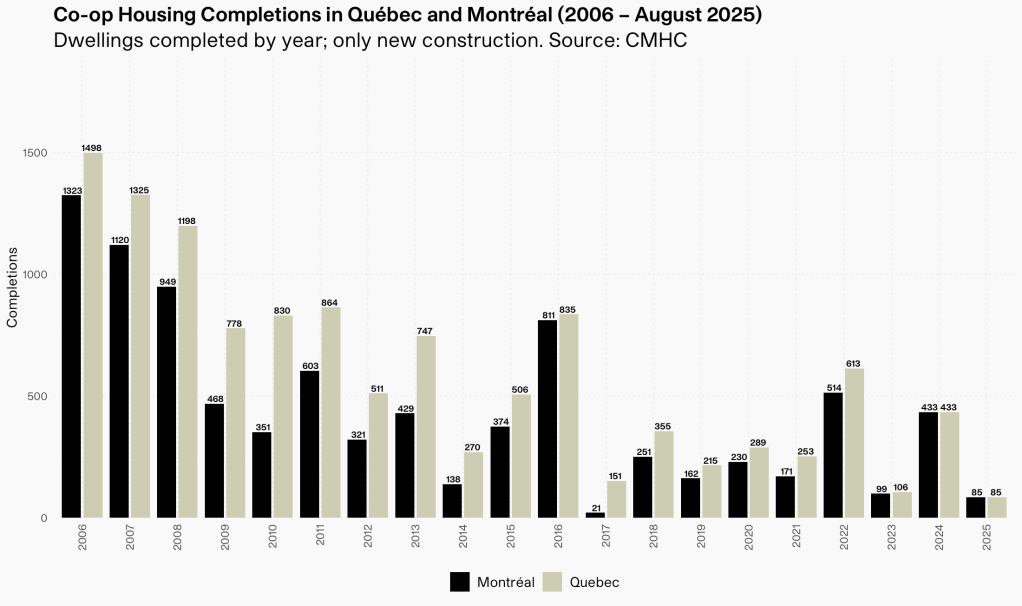

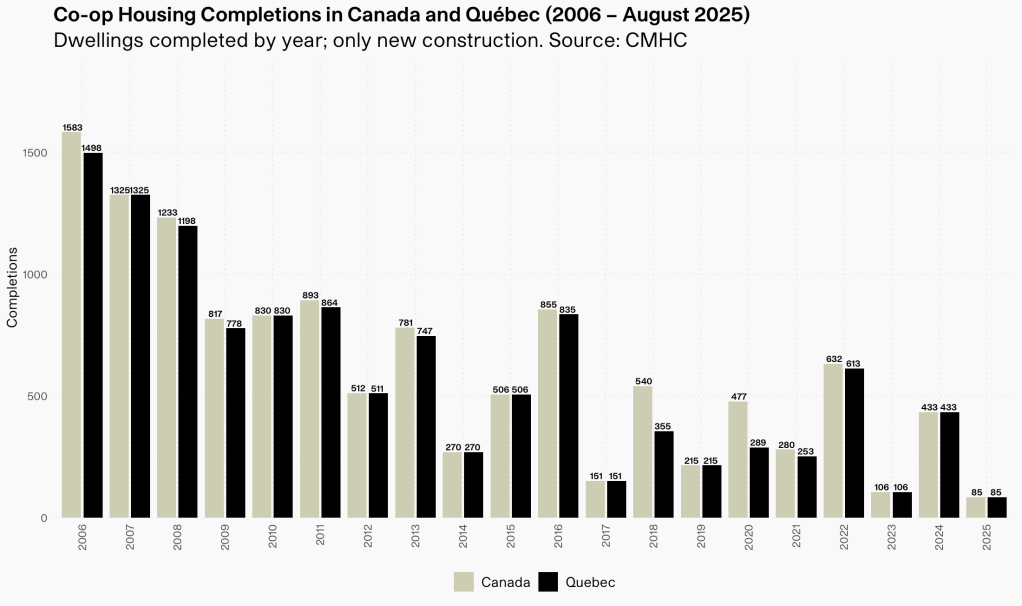

Montreal leads among Canadian cities in progressive cooperative housing practices (Ryan, 2023), if compared to major Canadian cities and their construction starts in 2017-2021 – 1,013 co-op units in Montréal, only 27 in Vancouver, 16 in Ottawa, and 0 in Toronto, Calgary and Edmonton (Whitzman, 2022), and since 2022 until August 2025 – 635 co-op units in Montréal, 11 in Edmonton and 0 in Vancouver, Ottawa, Toronto and Calgary (CMHC, 2025), and at the same time being famous for its civil mobilizations and Milton Parc housing cooperative that, since its establishment in the 1970s, advocated for funding and national and municipal policies for housing cooperatives in Canada (Bennett, 1997; Saillant, 2018, 2024; Suttor, 2016). However the 1990s shift, consistent with global neoliberal trends, of downloading responsibilities for housing programs to provinces, decrease in funding for social housing and support of homeownership for macroeconomic reasons had an overall damaging impact (Hulchanski, 2006; Prince, 1995) and put Montréal’s cooperative housing movement to a relative standstill and gradual weathering compared with other Western World mature cooperative movements, such as in Denmark, Germany and Switzerland. In Barcelona, on the other hand, while being clearly oriented on the creation of social capital and manifesting the cooperative movement values, the relatively young cooperative housing movement, established in 2010s, does not house those in the most housing need yet.

Therefore, in light of considerations mentioned above, it is crucial to understand how established and mature cooperative housing movement, such as the one in Montréal, is able to continue to cater to those in housing need while being restrained by global trends of neoliberal politics, together with challenges and successes of the new cooperative housing movement, such as the one in Barcelona, that is searching to cater to housing needs of the most in need, but is restrained by existing neoliberal politics, globally oriented real estate market and without the support of the mature cooperative system in place.

Some preliminary findings